With a little more time on my hands I've been thinking. I do that. Actually I've been reading and thinking, First on the reading list was a re-read of Sir Ken Robinson's book 'Creative Schools'. Several years ago I gifted a copy to every staff member, and try to continue this tradition, although supplies ran a little short this year so I have a few copies to catch up on. But the book captures a lot of what I think is important to schools.

Before I come to my main observation, allow me to list some readily apparent points that come from Sir Ken's writing:

- Creativity comes directly from our individual cultures, so it is essential that every one of us is able to connect with our own culture and heritage

- Personalisation is essential to creativity. That is, learners need to be able to find their 'element' (Sir Ken's term for that thing which excites us more than anything else)

- Relationships are absolutely essential to this personalisation.

Sir Ken defines creativity as ".. the process of having original ideas that have value." (Robinson, page 118). He goes on to say 'There are two other concepts to keep in mind: imagination and innovation. Imagination id the root of creativity. It is the ability to bring to ind things that aren't present to our senses. Creativity is putting your imagination to work. It is applied imagination. Innovation is putting new ideas into practice." (Robinson Page 118). He goes on to attack the myth that only some of us are creative, and comments that ".. Creativity is possible in all areas of human life, in science, the arts, mathematics, technology, cuisine, teaching, politics, business, you name it." (Robinson, Page 119).

The final piece of Sir Ken wisdom I;'d like to bring to this post is this. He says "Creativity is about fresh thinking. It doesn't have to be new to the whole of humanity - although that's always a bonus - but certainly to the person whose work it is" (Robinson, Page 119)

I now want to tie this in to our Manaiakalani pedagogy 'Learn Create Share'.

Here's how we define "Create|Hanga" within our Manaiakalani context: “Combine existing knowledge with original ideas in new and imaginative ways to create a new outcome.”

(Source: Staff presentation , Kelsey Morgan, 2020)

In my opinion the important synthesis of these ideas is this: when a learner brings together the ideas that she has come to understand, and develops a new insight into a specific topic, this is creativity. From my own subject discipline, if a learner brings together concepts of supply and demand, to arrive at the notion of the market, and its role in setting pieces and allocating resources, this is creativity. As Sir Ken observes, this is not an idea new to humanity, but it is new to the learner. Alternatively, if a learner studies a dramatic role, and then performs it with his own characterisation, that is creativity, even of the characterisation simply mimics that of another. Or if a learner suddenly understands the power of bisecting angles to slip through the defensive line of the opposing league or rugby team, this is creativity.

Creativity may well be seen directly in the 'creative arts (painting, music, drama, dance) but it can also be seen regularly in all other areas of human endeavour and study.

A group of students planing, and initiating, a community impact project that has them go out and plant 200 trees in a wetland is creativity if it represents a shift in their understanding that allows them to understand the importance of those trees to the local environment.

Our Hornby High School experiences along the path of being 'a centre of creative excellence' encompass a broad spectrum of what might be termed creative activity and experience.

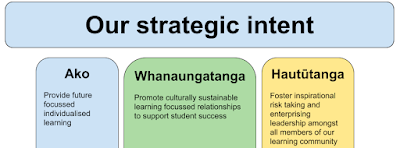

There is the aspect of 'creative teaching' Staff at Hornby High School are part the way along their own journey as we explore new and more effective ways of causing learning. A significant driver behind the changes that we have made is the desire, nay the absolute necessity, of increasing student engagement in their own learning. As Sir Ken says "The real driver of creativity is an appetite for discovery and a passion for the work itself." (Robinson, Page 120). We have so far restructured the school experiences of our Year 7-9 students, so that subjects are by and large not taught in isolation, but rather in a connected way. Our 'Hurumanu' are not yet perfect (and arguably never will be) but as we adapt and change we are modelling an essential ingredient of creativity, the willing ness to take risks, and to fail. We have already evolved our practice in this area in response to what has worked and what ha not. I continue to advocate for staff being prepared to take risks, and to fail. I continue to make the point that failure is more than OK, it is essential to everyone's learning.

We have carved time out of the week to build more meaningful relationships, relationships for learning, that will support student agency and efficacy. And we continue to work hard to build our cultural competence as a kura. "Cultural diversity is one of the glories of human existence." (Robinson, Page 49). All learners have a right to be themselves, to be able to express themselves as their own true authentic selves, at all times they are in our kura.

Then there is the quite different issue of teaching creativity. While on the surface this may have seemed to be the easiest of the two tasks, it is I suspect the more difficult. However when I see mathematics teachers encouraging students to have a go, focusing on method rather than the right or wrong answer, I know that even in what traditionally some might think as the most staid of disciplines we have the essential elements of creativity. After all the beauty and creativity implicit in mathematics is boundless.

Encouraging insight and imagination, encouraging risk taking and the willingness to put those new ideas out ther efor others to see, is essential to this work. As I write this I am sitting at a local suburban library where, right in front of me, are Year 3/4 students visualisations s of wintery trees. Look at this:

The sad thing is that we become less willing to do this as we grow older. There is a delightful story in one of the Sir Ken's TeD talks where he describes talking with a 5(?) year old who is intently drawing. He asks what she is drawing and she replies that she is drawing a picture of God. He responds that no one knows what God looks like, to which she says 'They will in a moment'. This unbounded willingness to take risks is something that we need to nurture and sustain as we grow.

My purpose in writing this is to try and give my colleagues the benefit of the brief time I have had to step back and look at what we are doing, what we are achieving. Are we 'a centre of creative excellence'? No. Are we on a journey that reflects pursuit of that as our vision? Yes, as we seek to try new things, as we seek to support our learners to take risks, as we undertake to be risk takers ourselves.

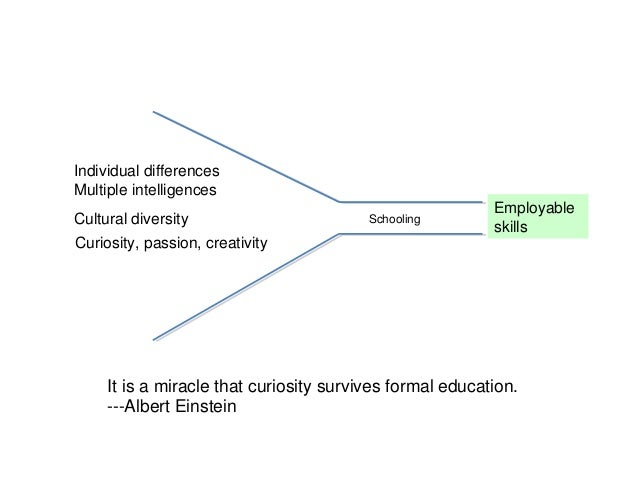

As I write this yet another report has been published criticising our schooling system, claiming that it has failed to improve results for learners in Aotearoa. In my opinion it reflects much more the degree to which the authors are out of touch with the new reality of the world around us in 2020, and the demands of that world as we embrace technologies that weren't even imagined beyond the minds of science fiction writers 20 years ago. That technology is rapidly replacing so many previously human tasks, in fact anything that is repetitive and at all predictable in our daily work. This is already accelerating in our current Covid world, as businesses are pushed ever faster to find new ways of doing things.

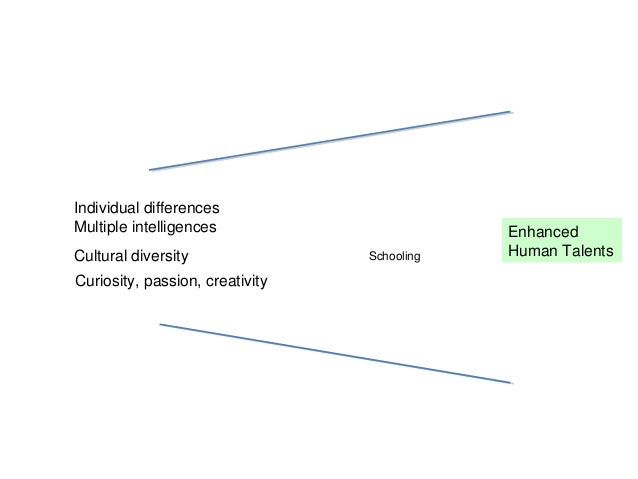

As the technology progresses we increasingly need to focus on those things that technology cannot replace, on those things that make us uniquely human, and it has been my contention for a number of years that one of those things is our creativity. Another of course is our ability to understand ourselves as human beings (to be introspective), and to empathise with each other. This requires a connection with who we are, what our origins are, our culture and our sense of belonging. These are the big jobs of our kura as we continue to forge ahead into this century.

The cultural component of this challenge is perhaps the most pertinent. The new report cites PISA data (something that I am frankly NOT enamoured with). My understanding of our PISA achievement data is that we are a population of two halves. Those of European origin in particular continue to perform as well as any students in the world. Our issue is our tail of under achievement, in which Māori and Pasifika learners are over represented. The challenge for us at both a systemic and a kura level is NOT the quality of the 'instruction' per se, it is a question of the cultural capability of our schools, one that I suggest goes back to our underlying structures. The current system does not work for all, it works for some. I would go as far as to express the opinion that it works for the privileged few. To persist with the system we have had, as the report writer might have us believe, is in my opinion little more than structural racism, as historical systems have continued to fail our Māori and Pasifka learners.'What's good for Māori is good for all'.

This includes an acceptance and celebration of the 'Māori world view' in science and maths, in literature and performing arts. We would be conceited indeed if we denied the power and efficacy of Māori mathematics and astronomy for example when as a people our Polynesian forebears were navigating and voyaging across vast tracts of the Pacific Ocean in ways Europeans dared not across their own oceans and seas, and mostly at times often well before Europeans were prepared to try. As I quoted above - "Cultural diversity is one of the glories of human existence."

So, for my colleagues at Hornby High School.. ka mau te wehi, he waka eke noa. Our progress has been significant, and I thank you for and celebrate your work, and your willingness to imagine and try new things.

As I often say, I am not interested in revolution for its own sake - revolutions all too often leave blood and bodies in the streets, I would much rather we take the path of evolution, as I am keen that we are all standing together along the way of this journey. One step at a time.

Ehara taku toa, he takitahi, he toa takitini (My success should not be bestowed onto me alone, as it was not individual success but success of a collective).

WE are the collective.

Robin Sutton

Tumuaki

Bibliography

Robinson, Kenneth 'Creative Schools", Penguin Books, 2015