One of the biggest philosophical tensions I have felt in leading a kura towards a vision as 'he puna auaha a centre of creative excellence' is what on the surface is the apparent conflict between our rules based culture and creativity. When creativity apparently demands the ability to think outside the square, to break the rules, it seems odd then (maybe even implausible) that we can do so when schools have so many 'rules'. It is a regular kōrero with some students .. 'why do I have to follow these rules, XXX (insert appropriate issue here) doesn't affect my learning'.

Perhaps it's all about the 'rules of the game'.

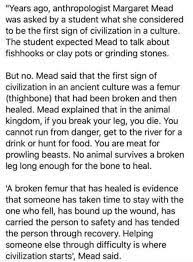

This has played on my mind. I have managed to come up with two arguments that reconcile these tensions. The first had been founded in what might turn out to be an 'urban myth', but I am still left wondering about the validity of the sentiment anyway. The story went like this.

Source: https://www.truthorfiction.com/margaret-mead-femur-quote/

I have had conversations with quite a few young people over the years in which I retold this story, making the point that for a group of hunter gatherer people to do this, there must have been some tacit agreement about how they would cooperate to 'feed the passenger', someone who was unable to do their share of hunting or gathering to feed themselves. Now there is a good argument to say that this story about Margaret Mead never happened. I'll go with that, but I still think there is some validity in the sentiment, and I would suggest that no group can be successful unless there is some tacit agreement about the rules that are necessary to ensure success. Regardless of the nature of the group - armed offenders squad, motorcycle gang, army platoon, school - I would posit that all groups need rules that are generally agreed upon and upheld if they are to be successful. If we then take the broader view of our purpose as schools, if we allow young people to walk out of our gates not understanding this need to follow a prescribed set of rules for success, then we have failed in a very profound way. We have not equipped those young people to take their place in society. Maybe the devil is in the detail about exactly what the rules should be, and how we agree upon and enforce them?

There is another argument that I rehearse in my mind that reconciles a rules based culture in support of creativity.

If we accept that creativity is founded on deep knowledge of a particular 'discipline', implicit in that deep knowledge must be an understanding of the rules of the discipline. What's more, if we intend to break the rules in a specific discipline in order to develop creative solutions, there is an argument that we need to know what those rules are. I'm less convinced by that last statement, but think that it is worth considering.

This takes me back to the latter years when I was teaching economics to senior students. I had fallen out of love with my discipline. I saw so many examples in which the theory and models I taught failed to match the real world. In order to continue to teach this material (required in NCEA standards) I would explain to students that the world needed them to challenge the orthodoxy, to challenge the rules, but in order to do so they needed to understand what those rules were in the first place. They needed deep knowledge of the theory and the models before they could critique them in any meaningful way (not that such a requirement seems to apply to journalists and politicians these days). It helped me, anyway.

So, where does this leave us? In my own mind I have been able to reconcile the rules based nature of kura as organisations and communities, with a vision that values and seeks to develop and grow creativity and creative thinking. Maybe I'm fooling myself?